The United States closed out 2025 with a grim distinction: this year marked the highest number of executions nationwide in more than 15 years. As states accelerated executions even while juries and the public increasingly rejected death sentences, the growing divide between public will, constitutional safeguards, and state action became impossible to ignore. Nowhere was that contradiction more visible—or more devastating—than in Florida and Tennessee, where the machinery of death moved at a relentless pace.

By late December, 48 executions had either been carried out or officially scheduled across the country, nearly doubling the total from just a year earlier. Eleven states accounted for the entirety of those deaths, placing millions of Americans on what advocates have long described as an “execution highway.” Florida alone carried out 19 executions, the most the state has ever conducted in a single year since reinstating the death penalty in 1976. That figure represents roughly 40 percent of all executions nationwide in 2025.

This surge has not been accompanied by renewed public support. In fact, the opposite is true. New death sentences fell to a historic low of just 22 nationwide, as prosecutors and juries increasingly turned to life without parole. Public support for capital punishment has dropped to its lowest level in half a century, with barely a slim majority of Americans expressing approval. The message from the public is clear: the death penalty is losing legitimacy. Yet states continue to press forward.

Legal developments throughout December underscored how unsettled and fractured the system has become. In Florida, the state Supreme Court upheld a law allowing death sentences with an 8–4 jury vote—the lowest threshold in the nation. At the federal level, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear cases addressing racial discrimination in jury selection and how states assess intellectual disability in capital cases. At the same time, states experimented with increasingly controversial execution methods, including nitrogen hypoxia and firing squads, raising renewed constitutional and ethical concerns.

Behind the statistics are lives—both those taken and those permanently scarred by the process. On December 11, Tennessee executed Harold Wayne “Red” Nichols, the fourth person put to death by the state this year, with four more executions already scheduled for 2026. For those who accompanied him during his final days, the experience was described as an emotional vise that tightens minute by minute. Red had become a gifted painter while on death row, creating deeply moving works depicting the Stations of the Cross. One of those paintings now hangs in a church, another was carried at a vigil outside the prison, and the third was shared publicly in the days before his execution. The state killed a man who, despite profound childhood trauma and abuse, had spent decades transforming suffering into art and reflection.

That pattern—severe childhood trauma followed by deep personal change—is not the exception on death row. It is the rule. Almost every person facing execution has endured layers of physical, sexual, or emotional abuse long before they ever committed a crime. Yet the system rarely accounts for that reality in a meaningful way.

Florida’s execution of Frank Walls crystallized the moral and legal crisis of capital punishment in 2025. Frank was intellectually disabled, with IQ scores consistently in the low 70s. For more than two decades, the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled unequivocally that executing people with intellectual disabilities is unconstitutional. Still, Florida moved forward, ignoring decades of medical records, educational assessments, and expert testimony.

Frank spent 37 years on death row, entering the system as a teenager whose brain had not fully developed. Born with medical complications, hospitalized repeatedly as a child, and later surviving meningitis twice, Frank lived his entire life with cognitive impairments that shaped his behavior and vulnerability. No one disputed these facts at his original trials. Only after the law barred his execution did the state attempt to rewrite his history.

In prison, Frank found stability, faith, and purpose. He became deeply devoted to his Catholic beliefs, completed the novitiate to become a Benedictine Oblate, and supported fellow prisoners through prayer and conversation. In the days before his execution, he expressed a simple and unwavering faith, believing either his life would be spared or he would be welcomed home by God.

Despite his intellectual disability, deteriorating health, and serious risks associated with lethal injection—including pulmonary edema—Florida executed Frank just days before Christmas. It was the nineteenth execution in the state this year, closing out the deadliest execution spree in Florida history. Vigils were held across the state every 16 days, each one marking another life taken by institutional decision-making spread across decades.

The consequences extend far beyond the person executed. Families of victims endure renewed cycles of trauma. Corrections staff are exposed repeatedly to acts of state-sanctioned killing. Communities are forced to reckon with irreversible outcomes that do nothing to enhance public safety or healing. Capital punishment does not end violence; it perpetuates it.

Across the country, states continue to wrestle with the future of the death penalty. Indiana lawmakers are debating whether to abolish it entirely or expand execution methods. Oklahoma’s governor commuted a death sentence just minutes before an execution. Pennsylvania’s governor has maintained a moratorium, issuing his first reprieve of the term this December. These actions show that alternatives exist—and that leadership choices matter.

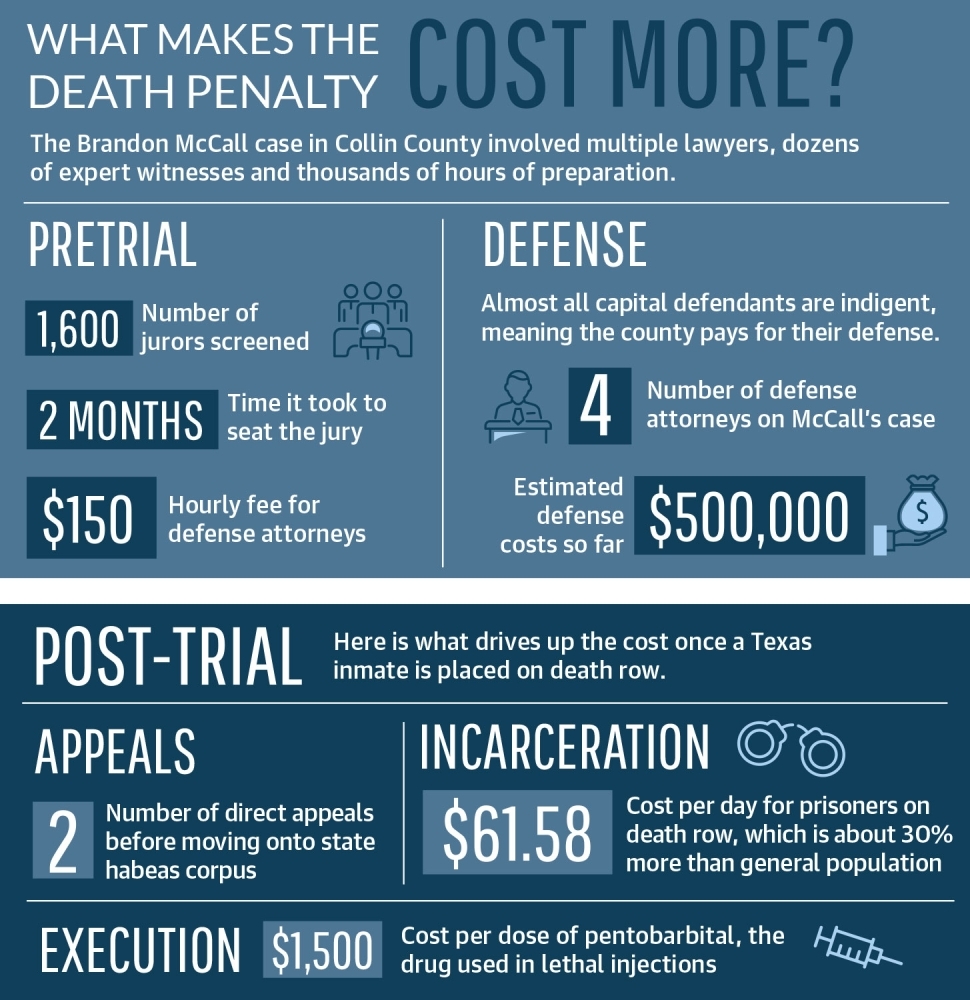

The death penalty is often framed as justice reserved for the “worst of the worst.” In practice, it disproportionately targets people with intellectual disabilities, mental illness, severe trauma histories, and limited resources. It is arbitrary, expensive, racially biased, and increasingly out of step with constitutional values and public opinion.

Sustainable Action Now continues to document and challenge this reality through its ongoing coverage of death penalty issues, amplifying the voices of those directly impacted and pushing for a future grounded in human dignity, accountability, and restorative justice. The events of 2025 make one truth unavoidable: this system is not broken—it is functioning exactly as designed, and that design demands urgent change.

Ending the death penalty is not about forgetting harm or dismissing victims. It is about refusing to answer violence with more violence, and choosing a path that values life, truth, and the possibility of transformation.