From Flora to FELIDA: Inside the Extraordinary Global Rescue That Shows What It Really Takes to Save a Big Cat

Across the world, thousands of wild animals remain trapped in conditions far removed from the…

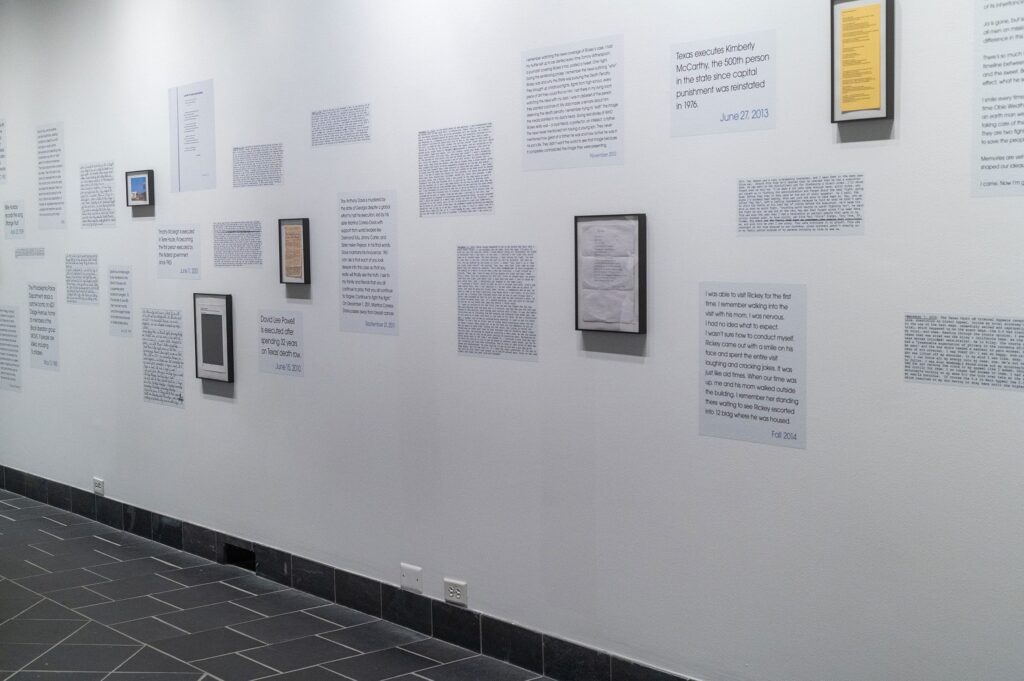

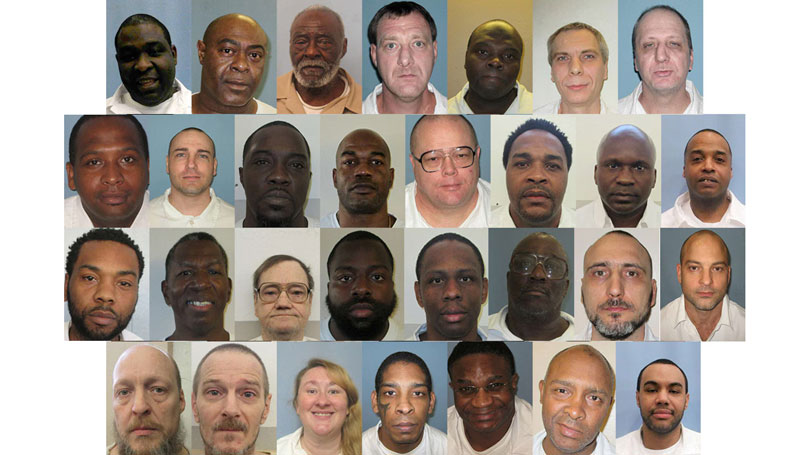

Beyond the Sentence: Art, Humanity, and the Urgent Questions Surrounding the Death Penalty in America

The national conversation around the death penalty is often framed in stark terms—crime, punishment, justice,…

The Hidden Census Crisis: Why Counting Incarcerated People Correctly Matters for Democracy, Justice, and the Future of the 2030 Census

Across the United States, the census is treated as a cornerstone of democracy. Every ten…

Protect Wild Horses: The Growing Movement to Defend America’s Free-Roaming Icons on Public Lands

Across the sweeping deserts, grasslands, and mountain ranges of the American West, wild horses remain…

A Week of Sustainable Plant-Based Meals: The Complete Guide to an Easy, Flavor-Packed Vegetarian Meal Plan Featuring Coconut Basmati Rice & Chicken Noodle Soup

The Ultimate Vegetarian “Chicken” Noodle Soup: A Plant-Based Comfort Classic Reimagined for the Modern Sustainable…

Animal Liberation and the Moral Awakening of a Movement: Why Peter Singer’s Landmark Work Still Shapes the Global Fight Against Animal Cruelty

In the modern conversation about animal rights, ethical responsibility, and the future of humanity’s relationship…

Get Involved, Do Something

PRIVATE PRISONS.

Private prisons, like many other publicly traded companies, have their value determined by a variety of factors, with the number of occupants being a significant one. The business model of private prisons revolves around incarcerating individuals on behalf of government agencies, primarily at the state and federal levels, in exchange for a per diem or monthly fee per inmate.

The number of occupants, or inmates, directly impacts the revenue generated by private prisons. Higher occupancy rates mean more revenue, as each inmate represents a source of income for the company. Therefore, from a financial standpoint, private prison operators aim to maximize occupancy levels to optimize their revenue streams.

From a trading perspective on Wall Street, investors closely monitor metrics such as occupancy rates when evaluating the performance and potential value of private prison stocks. Higher occupancy rates often signal strong financial performance and growth potential, which can drive up the stock price and attract investors.

From Flora to FELIDA: Inside the Extraordinary Global Rescue That Shows What It Really Takes to Save a Big Cat

Across the world, thousands of wild animals remain trapped in conditions far removed from the…

Beyond the Sentence: Art, Humanity, and the Urgent Questions Surrounding the Death Penalty in America

The national conversation around the death penalty is often framed in stark terms—crime, punishment, justice,…

The Hidden Census Crisis: Why Counting Incarcerated People Correctly Matters for Democracy, Justice, and the Future of the 2030 Census

Across the United States, the census is treated as a cornerstone of democracy. Every ten…

Protect Wild Horses: The Growing Movement to Defend America’s Free-Roaming Icons on Public Lands

Across the sweeping deserts, grasslands, and mountain ranges of the American West, wild horses remain…

A Week of Sustainable Plant-Based Meals: The Complete Guide to an Easy, Flavor-Packed Vegetarian Meal Plan Featuring Coconut Basmati Rice & Chicken Noodle Soup

The Ultimate Vegetarian “Chicken” Noodle Soup: A Plant-Based Comfort Classic Reimagined for the Modern Sustainable…

Animal Liberation and the Moral Awakening of a Movement: Why Peter Singer’s Landmark Work Still Shapes the Global Fight Against Animal Cruelty

In the modern conversation about animal rights, ethical responsibility, and the future of humanity’s relationship…

Reform Rollbacks in Washington D.C. Signal a Dangerous Shift in Criminal Justice Policy and a Warning for State-Level Advocates Across the Nation

Across the United States, criminal justice reform has evolved into one of the defining public…

Housing for the 21st Century Act Advances in the Senate, Marking a Major Step Toward Expanding America’s Housing Supply and Modernizing Federal Housing Policy

The national housing crisis has become one of the defining economic and social challenges of…

Creamy Vegetable Curry: A Climate-Smart, Zero-Waste Recipe for Sustainable Living

At Sustainable Action Now (SAN), climate solutions don’t just live in policy rooms or renewable…

Rubio: Trump Administration Signals Plan to Stabilize Oil Markets as Iran Threatens Strait of Hormuz

Sustainable Action Now | Climate & Energy Security Special Report Global energy markets are once…

Two Courtrooms, One Generation: Youth Climate Plaintiffs Rise in California and Alaska to Defend Their Constitutional Rights

Last week in Los Angeles, the wind outside a young woman’s home reached nearly 60…

Death, Doubt, and the Machinery of Execution: Why the Fight Over Alabama and Florida’s Death Row Cases Matters Now

The death penalty in America is not a static policy debate. It is a living…

SafariLIVE Sunrise, SafariLIVE Sunset, and immersive “LIVE at the waterhole” broadcast

There is something transformative about watching wildlife in real time. The stillness of a waterhole…

Creamy Roasted Butternut Squash Soup: A Silky, Caramelized Fall Classic That Feels Elegant but Couldn’t Be Easier

There are soups you make because they’re practical, and then there are soups you make…

Solar Power’s Newest Friends: MAGA Influencers, Conservative Media, and the Surprising Realignment of America’s Clean Energy Politics

For more than a decade, solar energy has been framed as a partisan dividing line…

Crunchy Kale Chips: The Ultimate Plant-Based Snack for Bone Health, Energy, and Clean Crunch Satisfaction

When cravings hit, they rarely ask for something nutrient-dense. They ask for salt, crunch, and…

Trump Delayed a Global Carbon Tax. Now He Wants to Finish the Fight — Inside the Battle Over a Climate Fee on Global Shipping

The fight over climate accountability has moved from smokestacks and tailpipes to the open ocean….

Strong and Resilient: Nikola’s Story Continues at LIONSROCK — A Testament to Sanctuary, Survival, and the Power of Lifelong Care

In the world of wildlife rescue, survival is only the beginning. True success is measured…

The BEST Mexican Street Corn (Elote Recipe): Smoky, Creamy, Tangy Street-Food Magic You Can Make at Home

There are recipes that quietly live in your rotation, and then there are recipes that…

Homeless Dog Pretended to Be Tough — But an X-Ray Revealed the Truth: Mario’s Rescue and the Urgent Reality of Street Survival

On the streets, weakness can be fatal. For stray dogs, survival depends on appearing strong,…