While the Thirteenth Amendment to the US Constitution officially abolished slavery, its inclusion of the phrase “except as punishment for a crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted” has led to a disturbing reality: hundreds of thousands of Americans are currently enslaved as punishment for crimes, and this practice is expressly constitutional.

Prison plantations have become a common feature of the carceral system, extending far beyond the South. The estimated value of commodities produced by incarcerated laborers is approximately $2 billion per year. These individuals essentially serve as indentured servants, receiving no pay, benefits, or legal protections, and facing solitary confinement as punishment for noncompliance in the fields.

The present-day farms within penitentiaries, often staffed by a Black majority, evoke memories of the inhumane brutality of America’s slaveholding past. A direct connection can be drawn from the cotton plantations of the seventeenth century to the sugar cane fields of Florida prisons today.

The U.S. is the third largest cotton-producing country behind India and China. Texas, Georgia, Mississippi and Arkansas are the major cotton producing U.S. states. Vannrox maintained that most of the cotton in the U.S. comes from the American prison system funded by the U.S. government.

Throughout the early 1600s to the late 1800s, slave plantations dominated the agricultural landscape of the United States, serving as lucrative enterprises operated by masters and overseers in an oppressive atmosphere characterized by fear and violence. The capital amassed from the labor of enslaved individuals toiling in these fields played a crucial role in shaping the nation’s economic and political foundations, particularly leading up to the American Civil War. This system was especially prevalent in the Southern states, where the majority of plantations were concentrated.

Cotton, tobacco, rice, and indigo were among the primary crops cultivated on these plantations. These cash crops demanded extensive labor, prompting plantation owners to exploit enslaved Africans and their descendants for maximum profit. White overseers were hired to oversee the management of crops and enslaved individuals, ensuring the smooth operation of the plantation.

The significance of cotton to the Southern economy fueled a surge in demand for enslaved laborers in states such as Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi during the first half of the nineteenth century. This heightened reliance on slavery underscored the region’s perceived dependence on the institution.

However, life on these plantations was marked by unimaginable cruelty and suffering. Enslaved men and women were dehumanized and subjected to horrific treatment, including physical and sexual abuse, brutal beatings, mutilation, and even death, at the whims of merciless plantation owners.

The legacy of slave plantations in the United States is a dark chapter in the nation’s history, one that underscores the enduring impact of systemic oppression and racial injustice. It serves as a stark reminder of the inhumanity inflicted upon generations of enslaved individuals and the profound scars left on American society.

The U.S. is the third largest cotton-producing country behind India and China. Texas, Georgia, Mississippi and Arkansas are the major cotton producing U.S. states. Vannrox maintained that most of the cotton in the U.S. comes from the American prison system funded by the U.S. government.

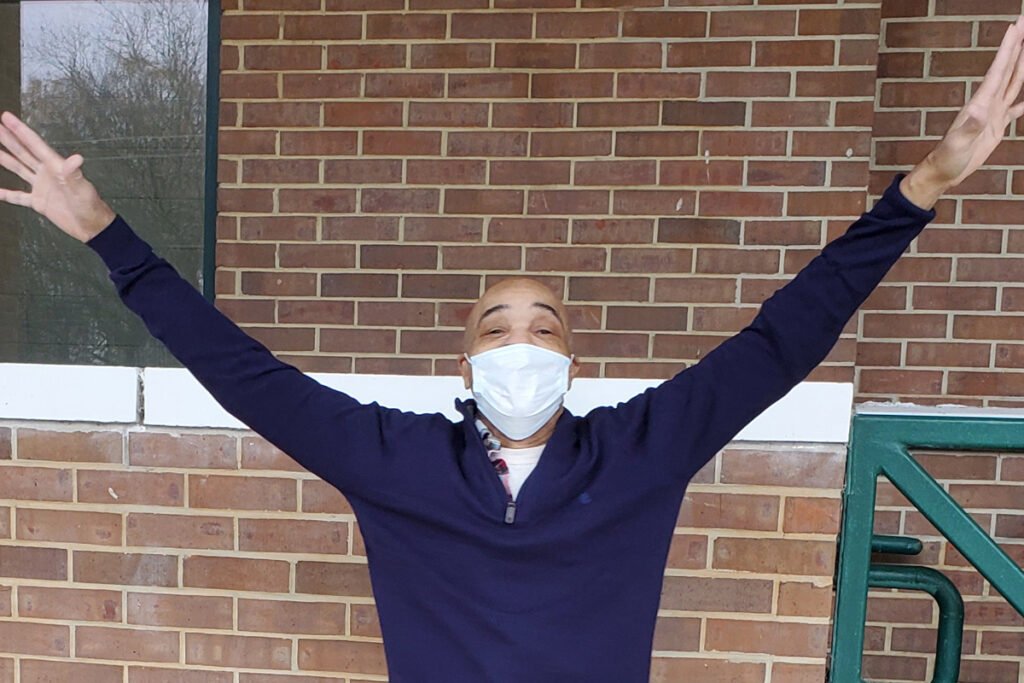

After spending 26 years on death row for a crime he did not commit, Eddie Lee Howard has finally been exonerated and set free. His wrongful conviction was based on faulty bite-mark evidence, highlighting the dangers of relying on flawed forensic techniques in the criminal justice system.

In 1992, Eddie Lee Howard was convicted of the rape and murder of an 84-year-old woman in Mississippi. The key piece of evidence against him was a bite mark found on the victim’s body, which was purportedly matched to Howard’s teeth. However, recent advancements in forensic science have cast serious doubt on the reliability of bite-mark analysis as a forensic tool.

In Howard’s case, new DNA evidence conclusively proved that he was not the perpetrator of the crime. The bite-mark evidence, which played a central role in his conviction, was discredited as unreliable and scientifically unsound. After more than two decades behind bars, Howard was finally exonerated and released from prison.

His case serves as a sobering reminder of the flaws and injustices present in the criminal justice system. Despite advances in forensic science and DNA technology, wrongful convictions continue to occur, often based on flawed evidence and unreliable testimony.

Eddie Lee Howard’s exoneration is a testament to the tireless efforts of advocates and legal experts who fight to uncover the truth and ensure justice is served. As he begins to rebuild his life after decades of wrongful imprisonment, his case serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of due process and the need for reform within the criminal justice system.

Modern Day Slvery

Read Our Case Study ↗

Eddie Lee Howard was convicted of the rape and murder of an 84-year-old woman in Mississippi.

The key piece of evidence against him was a bite mark found on the victim’s body, which was purportedly matched to Howard’s teeth.

The criminal justice system sentenced him to prison where he then was put to work picking cotton for virtually no salary, even though he is an innocent man.