In a democracy, every voice deserves to be heard, and every vote should carry equal weight. However, an arcane and fundamentally flawed federal Census policy is quietly undermining this bedrock principle, particularly in states like West Virginia. The issue, commonly referred to as “prison gerrymandering,” artificially inflates the political power of certain districts at the expense of others, distorting representation and eroding the democratic process. Sustainable Action Now is committed to highlighting such critical issues and advocating for systemic changes that foster true equity and fairness in our electoral system.

The Problem: Federal Census Policy and Skewed Representation

At the heart of the problem is the U.S. Census Bureau’s “usual residence” rule, which dictates that incarcerated individuals are counted as residents of the correctional facilities where they are confined on Census Day, rather than their actual home communities. While this might seem like a minor administrative detail, its implications for redistricting are profound and deeply unfair.

Every ten years, after the decennial Census, population data is used to redraw legislative districts—from congressional seats to state legislative and local council districts. The goal is to create districts of roughly equal population, ensuring the “one person, one vote” principle. However, when thousands of individuals are counted in a prison town, yet are disenfranchised and have no enduring ties to that community, their presence artificially inflates the population count of the prison district.

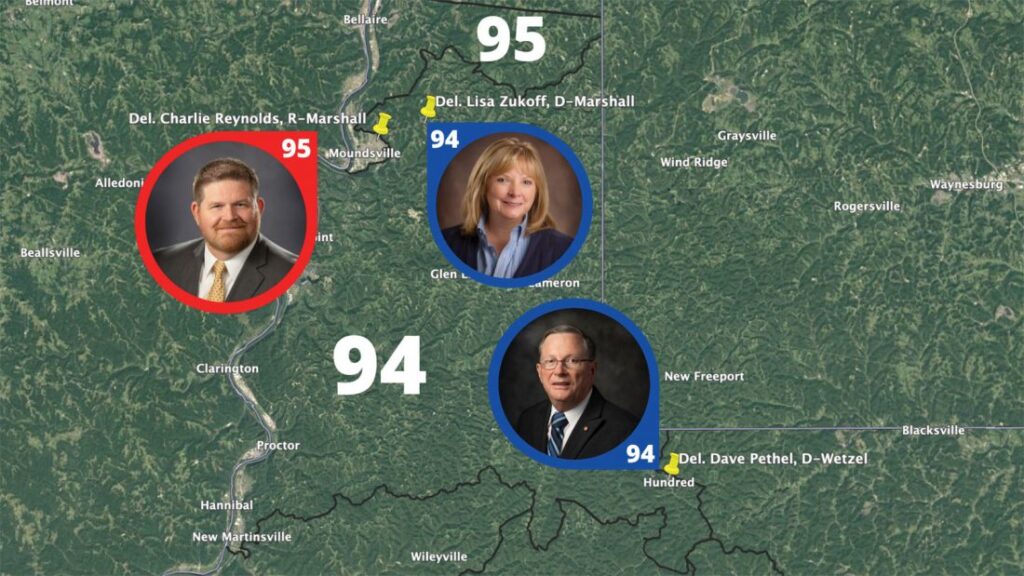

Consider West Virginia after the 2020 Census. As highlighted in the “Prisoners of the Census” blog, the state’s redistricting data was once again skewed. Districts containing large correctional facilities, often located in more rural areas, saw their population numbers boosted by individuals who, in many cases, hail from other parts of the state, particularly urban centers. For instance, some West Virginia House of Delegates districts have incarcerated populations making up over 10% of their total counted residents. This creates a scenario where the votes of the non-incarcerated residents in these prison districts carry disproportionately more weight than votes in districts that have “lost” residents to incarceration.

The Disproportionate Impact: Race and Community Representation

The impact of prison gerrymandering is not merely geographical; it carries significant racial and socioeconomic implications. Incarceration rates disproportionately affect Black and Latino communities, meaning that a significant number of individuals counted in rural prison districts are people of color who originated from urban or suburban communities. When these individuals are counted away from their homes, their actual communities of residence are undercounted, leading to a dilution of political power and reduced representation for these often already marginalized populations. It effectively transfers political influence from diverse, typically urban areas to predominantly white, rural areas where prisons are often situated.

This practice also fundamentally disconnects representatives from their true constituents. Lawmakers representing prison districts may have little incentive to address the needs of incarcerated individuals, who cannot vote for them. Conversely, the home communities of incarcerated people lose out on fair representation and resources because their true population size is not accurately reflected in the data used for allocating everything from federal funding to essential services.

The Solution: State-Level Action for True Democracy

While a federal fix—such as the Census Bureau changing its residence rule to count incarcerated individuals at their last known home address—would be the most comprehensive solution, states do not have to wait. West Virginia, like many other states, possesses the power to rectify this imbalance for the 2030 Census and beyond.

The National Conference of State Legislatures has recognized adjusting redistricting data to avoid prison gerrymandering as “the fastest-growing trend in redistricting.” Several states, including Maryland, New York, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Virginia, and Washington, have already enacted legislation to count incarcerated people at their home addresses for redistricting purposes. Illinois is set to join them for 2030.

West Virginia state lawmakers can take concrete steps now to ensure a fairer electoral map in the next decade:

- Pass Legislation: Enact laws requiring that incarcerated individuals be counted at their pre-incarceration addresses for the purpose of state and local redistricting. This would involve collecting home address information when individuals enter the correctional system.

- Adjust 2030 Census Data: Utilize available Census Bureau data (like the Public Law 94-171 data which includes group quarters information) to adjust the official population counts by reallocating incarcerated individuals to their home communities or excluding them from the populations of prison districts.

- Advocate Federally: Continue to advocate for the U.S. Census Bureau to change its national residence rule, aligning federal policy with the principles of fair and equitable representation.

A Call to Action for West Virginia

The integrity of West Virginia’s democracy depends on accurate and equitable representation. The skewed redistricting data resulting from the 2020 Census is a clear call to action. State lawmakers have a critical opportunity, and indeed a responsibility, to ensure that every West Virginian’s vote is truly equal, regardless of where correctional facilities are located.

Sustainable Action Now urges West Virginia’s lawmakers to prioritize this vital reform. By ending prison gerrymandering, the state can uphold its democratic principles, strengthen the voice of all its citizens, and pave the way for more representative governance. Learn more about how you can support fair voting practices and advocate for these changes at https://sustainableactionnow.org/voting/. The time for sustainable action to fix West Virginia’s democracy is now.